-

Funerary relief bust

3rd century (dated 231 CE)

Limestone

H x W x D (overall): 60.1 x 55.3 x 23 cm (23 11/16 x 21 3/4 x 9 1/16 in)

The inscriptions carved on this relief bust, written in Aramaic, identify the figure as a woman named Haliphat and date her death to the year 231 C.E. The bust is from Palmyra, a city in southern Syria that flourished during the Roman Empire as a caravan oasis on the trade route linking the Mediterranean with West and Central Asia.

Many members of Palmyra's prosperous merchant class commissioned such funerary busts depicting fashionably dressed individuals; women often wear elaborate jewelry. The busts covered the openings of burial compartments in family tombs located in the desert outside Palmyra.

-

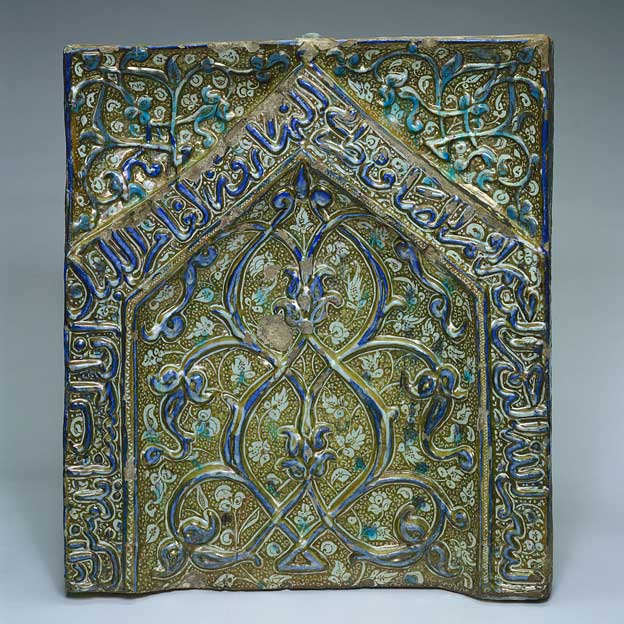

Panel from a mihrab

Il-Khanid dynasty, early 14th century

Molded stone-paste; painted under glaze with color and over glaze with luster

H x W x D (overall): 66.4 x 59 x 10.7 cm (26 1/8 x 23 1/4 x 4 3/16 in)

This glazed panel, adorned with an arabesque design in relief, originally formed the upper section of large tile mihrab. It is inscribed with a verse from the Qur'an (sura 11, verse 114):

In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate.

Perform prayer morning and evening, and in the watches

of the night. Behold, good works and drive away evil.

-

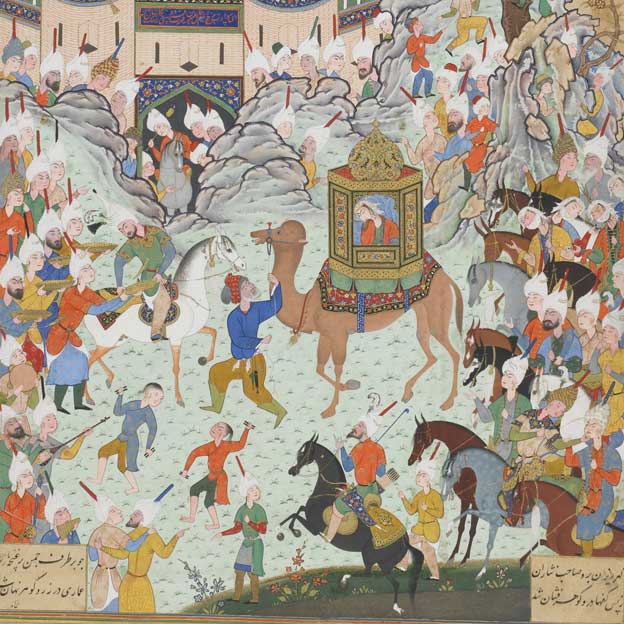

Folio from a Haft awrang (Seven thrones) by Jami (d.1492); verso: the Aziz and Zulaykha enter the capital of Egypt and the Egyptians come out to greet them; recto: text

Safavid period, 1556-1565

H x W: 34.2 x 23.2 cm (13 7/16 x 9 1/8 in)

According to the poet Jami, Zulaykha's love for Yusuf is kindled by dreams of a radiant and strikingly handsome youth. Thinking that he is the governor (aziz) of Egypt, Zulaykha is delighted when her father arranges her marriage to the governor and sends her to Egypt. Upon her arrival, Zulaykha realizes with great despair that the governor is not her beloved.

The exuberant composition celebrates the arrival of Zulaykha and her large retinue at the gates of Egypt. The joyous, festive mood may well refer to the arrival of Sultan Ibrahim Mirza's royal cousin and future wife, Gawhar-Sultan Khanim, the eldest daughter of Shah Thamasb, in Mashhad in 1556.

-

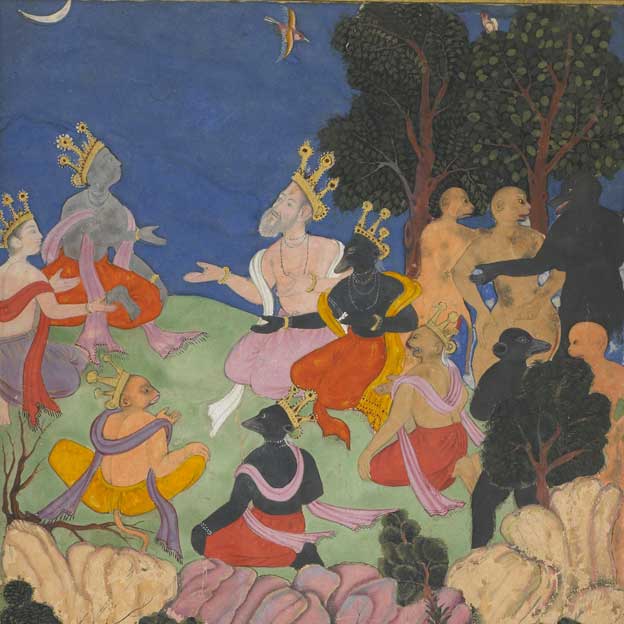

The Ramayana (Tales of Rama; The Freer Ramayana), Volume 2

Mughal dynasty, Reign of Akbar, 1597-1605

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, in modern bindings

H x W: 27.5 x 15.2 cm (10 13/16 x 6 in)

-

Sheep and Goat

Artist: Zhao Mengfu 趙孟頫 (1254-1322)

Yuan dynasty, ca. 1300

Ink on paper

H x W (image): 25.2 x 48.7 cm (9 15/16 x 19 3/16 in)

Zhao Mengfu was the preeminent painter and calligrapher of the early Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), and one of the most versatile and subtle artists in the Chinese tradition. Balanced in mood and posture, the two animals turn their heads back toward each other to create an open but unified composition. In his inscription at the left of the painting, Zhao Mengfu states his motivation for creating this work: "I have painted horses before, but have never painted sheep [or goats]. So when Zhongxin requested a painting, I playfully drew these for him from life. Though I cannot get close to the ancient masters, I have managed somewhat to capture their essential spirit."

The seals of several Ming and Qing dynasty collectors, especially those of the Qianlong emperor (reigned 1735-95), who once owned the scroll, are applied over much of the remaining paper. Borrowing vocabulary from an ancient poem about sheep, the emperor also provided the title frontispiece at right, which reads: "Divine likeness [of sheep] in motion and repose."

-

Nymph of the Luo River

Artist: Traditionally attributed to Gu Kaizhi (傳)顧愷之 (ca. 344-ca. 406)

Southern Song dynasty, mid-12th to mid-13th century

Ink and color on silk

H x W (image): 24.2 x 310.9 cm (9 1/2 x 122 3/8 in)

This handscroll illustrates a long rhapsody, or prose-poem (fu), written in 222 C.E. by the poet and prince Cao Zhi (192-232 C.E.), in which he describes his romantic encounter with the nymph, or goddess, of the Luo River in central China. Slightly less than half the work's original length, this scroll is one of the three important Song copies--the other two are in China in the Palace Museum, Beijing, and the Liaoning Provincial Museum--of an original composition traditionally attributed to the fourth-century pioneering figure Gu Kaizhi.

In this narrative scroll, figures are disproportionately large in relation to the landscape in which stylized elements are little more than stages set for various plots, and represent the beginning in the development of Chinese landscape painting. In this section, the goddess mounts her dragon-drawn chariot and departs over the waves, attended by a retinue of fantastic creatures.

-

Durga slaying the Buffalo Demon

Central Javanese Period, 9th century

Stone

H x W x D: 54.5 × 25.4 × 17 cm (21 7/16 × 10 × 6 11/16 in)

Goddess Durga was created from the combined energy of the three most powerful Hindu gods--Shiva, Brahma, and Vishnu--in order to defeat a demon that was plaguing the universe. This image represents a heroic moment for the goddess: she has just conquered the terrifying demon Mahisha. In order to escape the goddess, Mahisha had taken the form of a buffalo. Durga saw right through this petty disguise and caught him. The four-armed goddess stands on the buffalo's back, her upper hands holding the chakra (right) and conch (left). In her lower hands she holds a rope firmly tied to the buffalo's tail and to the hair of the demon Mahisha. The demon in human form emerges from the wound in the buffalo's neck, with his right leg remaining inside the animal's body. She conveys her triumph with calm certitude, her lips forming the suggestion of a smile. Her chin is tilted upwards and she gazes forwards through almond-shaped eyes. Durga wears an ankle-length sarong tied with sashes and a belt, thick bangles on her ankles and wrists, necklaces, earrings, and a diadem. Her face is framed by a halo roughly carved against a flat back-slab. This form of Durga is called Mahishasuramardini, which means "She who conquered the demon named Mahisha."

-

Naga ring

Bangkok period, 19th century

Gold

H x W x D: 3.5 × 3 × 1.5 cm (1 3/8 × 1 3/16 × 9/16 in)

Prevalent throughout South and Southeast Asian art, serpents, called nagas, are positive symbols. They are the guardians of the watery underworld, where they reside in jeweled palaces and protect corals and pearls. In Southeast Asia, nagas also represent the bridge that connects the human and divine worlds.

Exquisitely fashioned from 22 carat gold, the ring takes the shape of a coiled naga. The tip of its tail lies close beside the band, and the body spirals around the finger. It culminates in a powerful face with bulging eyes, upturned snout, and mouth with fanged teeth and extended tongue. The serpent's scales are individually articulated along the full surface. Left intentionally loose by the artisan, the tongue moves in and out, simulating a living creature.

Large and imposing in appearance, this ring was an elite commission. The auspicious naga design was exclusive to the Thai royal family, the serpent's potency and power befitting of a king. The ring was most likely made for or on behalf of King Rama V, the legendary King Chulalongkorn who ascended the throne in 1868 and ushered Thailand into an era of reform and democracy. Cosmopolitanism characterizes King Rama V's prolific artistic and architectural enterprises. Through motifs such as the naga, his commissions further reflect Thailand's deep historical connections across South and Southeast Asia.

-

Water-Moon Avalokitesvara (Suwol Gwaneum bosal)

Goryeo period, mid-14th century

Ink, color and gold on silk

H x W (image): 98.3 x 47.7 cm (38 11/16 x 18 3/4 in)

This painting, executed in ink, colors, and gold on silk, follows the same Chinese prototype as numerous other surviving examples executed in Korea during the late Goryeo period. The willow branch is held in a small vase to the side of the Bodhisattva. The small figure in a devotional pose may represent an allusion to passage in the Avatamsaka sutra. The details of this painting, from the elegant pose of the deity to the delicate use of color to render elements of the costume are characteristic of Korean Buddhist painting at the peak of its development. Touches of gold highlight the landscapes in a typically decorative manner.

-

Waves at Matsushima

Artist: Tawaraya Sōtatsu 俵屋宗達 (fl. ca. 1600-1643)

Edo period, 17th century

Ink, color, gold, and silver on paper

H x W (overall [each]): 166 x 369.9 cm (65 3/8 x 145 5/8 in)

The brilliant paintings on this pair of folding screens are regarded as masterpieces among only six surviving sets of screens by Sotatsu, a talented and innovative artist who headed a painting workshop known as Tawaraya. As a townsman, Sotatsu produced paintings such as fans for popular consumption. By the late 1620s, however, Sotatsu was painting for the imperial court, and his works survive in the collections of the Kyoto imperial palace. For his artistic merit, he was granted the honorary Buddhist ecclesiastical title Hokkyo (Bridge of the Law), which is included in his signature on these screens.

Matsushima (Pine Islands) is the name of a famous site (meisho) near Sendai, a city in Miyagi Prefecture in northeastern Japan. Its beauty inspired both poets and painters. In Sotatsu's screens the rock from which pine trees grow are rendered in brilliant mineral colors of green, blue, and brown, highlighted with gold. Waves in animated forms are delineated in alternating lines of ink and gold, producing a luminous effect. Clouds and embankments are rendered in particles of gold leaf accented with silver, which has darkened over time to a soft black tone.

Sotatsu's innovative composition creates a dynamic interplay among the land and cloud forms, the bending pines, and churning waves. His lifelong interest in pictorial composition left a lasting legacy. Later painters of the Rimpa school, such as Ogata Korin (1658-1716), repeated the Matsushima theme in their work. The Matsushima screens were probably painted in the early Kan'ei era (1624-44), a period of cultural efflorescence in Kyoto.

-

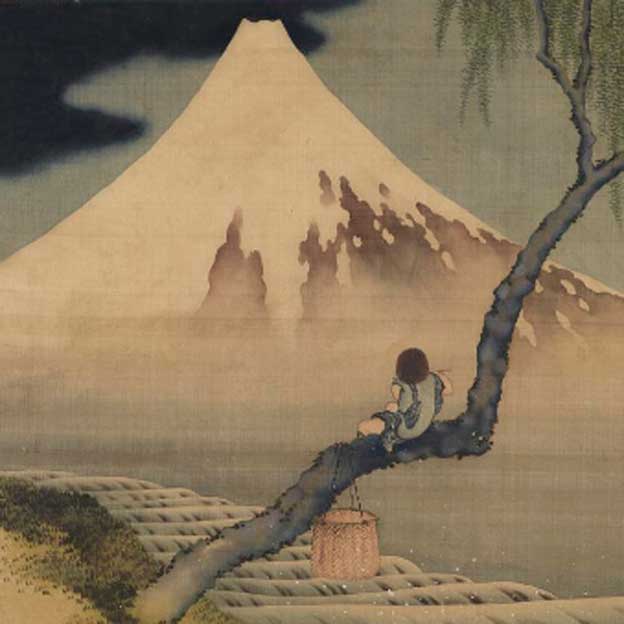

Boy Viewing Mount Fuji

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai 葛飾北斎 (1760-1849)

Edo period, 1839

Ink and color on silk

H x W (image): 36.2 x 51.3 cm (14 1/4 x 20 3/16 in)

Mount Fuji may be the most widely recognized symbol of Japan. The mountain and its name carry many meanings that are conveyed in Japanese by writing "Fuji" with different characters, such as a pair meaning "peerless." The highest mountain in Japan, Fuji's imminent power is contained in its seething volcanic core, hidden beneath its perennial cloak of snow. Regarded as sacred, Mount Fuji has been a site for religious pilgrimage, and ancient stories maintain that an elixir of immortality could be found at its peak. This painting frames the mountain in the bend of a willow that extends over a rushing stream. A young boy nestles in the tree, playing a flute while gazing at the mountain. This tranquil and engaging view of Fuji was one of hundreds produced by Hokusai during his lifetime. Here, at the age of nearly eighty, the artist gives visual form to his quest for long life by portraying a young boy in the thrall of the immortal mountain.

A prolific and technically proficient painter, Hokusai had a special sympathy for common people, whom he often depicted in his paintings, prints, and illustrations for printed books. Here he employs thin washes of color almost without outline to bring forth the familiar form of the great volcanic mountain.

-

Subodh Gupta: Terminal

October 14, 2017 to February 3, 2019

Sackler pavilion

Internationally acclaimed artist Subodh Gupta transforms familiar household objects, such as stainless steel and brass vessels often found in India, into wondrous structures. The Freer|Sackler features the artist’s monumental installation Terminal. Composed of towers of brass containers connected by an intricate web of thread, Terminal converts the readymade into a glimmering landscape. Ranging from one to fifteen feet tall, the spires recall architectural features found on religious structures such as churches, temples, and mosques. This exhibition is part of the Freer|Sackler’s contemporary art program.

-

Canteen

Ayyubid period, mid-13th century

Brass, silver inlay

H x W (overall): 45.2 x 36.7 cm (17 13/16 x 14 7/16 in)

This large, impressive canteen, the only known example of its kind from the Islamic world, recalls the shape of ceramic pilgrim flasks. Its inlaid silver decoration combines calligraphy and decorative motifs, such as intricate geometric designs, and lively animal scrolls, with Christian imagery. These include a representation of the Virgin and Child in the center, surrounded by narrative scenes from the life of Christ as well as saints and knights. It has been suggested that the canteen may have been commissioned by a wealthy Christian, perhaps, as a special memento of his travels.

-

Canteen

Ming dynasty, early 15th century

Porcelain with cobalt pigment under colorless glaze

H x W x D (overall): 46.9 x 41.8 x 21.3 cm (18 7/16 x 16 7/16 x 8 3/8 in)

The large, flat expanses and sharp angles natural to a metal shape are difficult to translate into porcelain clay, which, when so forced, tends to warp and crack during firing. This porcelain canteen is one of a group of blue-and-white ceramics, that may have been made for a Chinese clientele fascinated by Islamic metalware forms. The hybrid decoration on this canteen combines waves, a common Chinese motif; Chinese floral scrolls that seem to reflect awareness of Islamic arabesques; and an Islamic eight-pointed star on the central boss. Like its metal counterpart, the back of this canteen bears a socket, but it is uncertain whether this porcelain vessel, far heavier than the metal version, was ever used. It may have been a purely ornamental piece.

-

Square lidded ritual wine container (fangyi) with taotie, serpents, and birds

Early Western Zhou dynasty, ca. 1050-975 BCE

Bronze

H x W x D: 35.3 x 24.8 x 23.3 cm (13 7/8 x 9 3/4 x 9 3/16 in)

Despite the beauty of its decoration, with elaborate taotie patterns and animal motifs rendered in different levels of relief, this vessel is most famous for its lengthy cast inscription of 187 characters. The text, one of the longest from the early Zhou period, is repeated inside the vessel and the lid. A court scribe named Ling might have composed the text himself; the cast inscription resembles the rhythm and flow of calligraphy. If so, he could have been following a family tradition: he was a younger relative of Da, who was responsible for the fangding (F1950.7) in the Freer collection.

The vessel commemorates three days of administrative meetings and ritual ceremonies held in Chengzhou during the reign of Zhao, the fourth Zhou monarch. Mingbao, the son of the Duke of Zhou and a nephew of the Taibao, led the events, which began with a massive gathering of court and regional officials and concluded with offerings of animal sacrifices. Afterwards, in appreciation of their efforts, Mingbao awarded ritual wine, “metal” (probably bronze), and oxen to Ling and his colleague Captain Kang, with the order that the gifts be used for ritual purposes.

-

Square ritual food cauldron (fangding) with serpents and taotie

Early Western Zhou dynasty, ca. 1050-975 BCE

Bronze

H x W: 26.3 x 15.8 cm (10 3/8 x 6 1/4 in)

Clearly visible on one of this vessel’s long sides is a cast inscription that records events associated with a key figure in early Zhou history: the Grand Protector or “Taibao,” Duke Shi of Shao. Since this fangding mentions the Taibao’s role in creating commemorative cauldrons dedicated to Wu and Cheng, the first two Zhou kings, it was probably made during the reign of the third king, Kang. A scribe or chronicler named Da must have somehow assisted the Taibao in this or another effort; according to the inscription, he received a white horse for his service. Virtually the same text recurs on three similar fangding, indicating they were made as a functional set of food vessels.